Science fiction was born in the pulps, an ingenious medium credited to Frank Munsey that utilized the then-new high-speed printing presses to print on cheap, untrimmed, pulp paper, resulting in low-priced magazines. It was by way of these cheap pulps that sf began to emerge as a self-conscious genre, despite the repeatedly recycled clichéd stories. Superhero comics evolved alongside the sf pulps. They depict latter-day surrogate gods and goddesses, whether human, alien, or mutant.

As a seasonal treat, I would like to survey the changing depictions of Santa Claus on these covers.

(Click any image to enlarge)

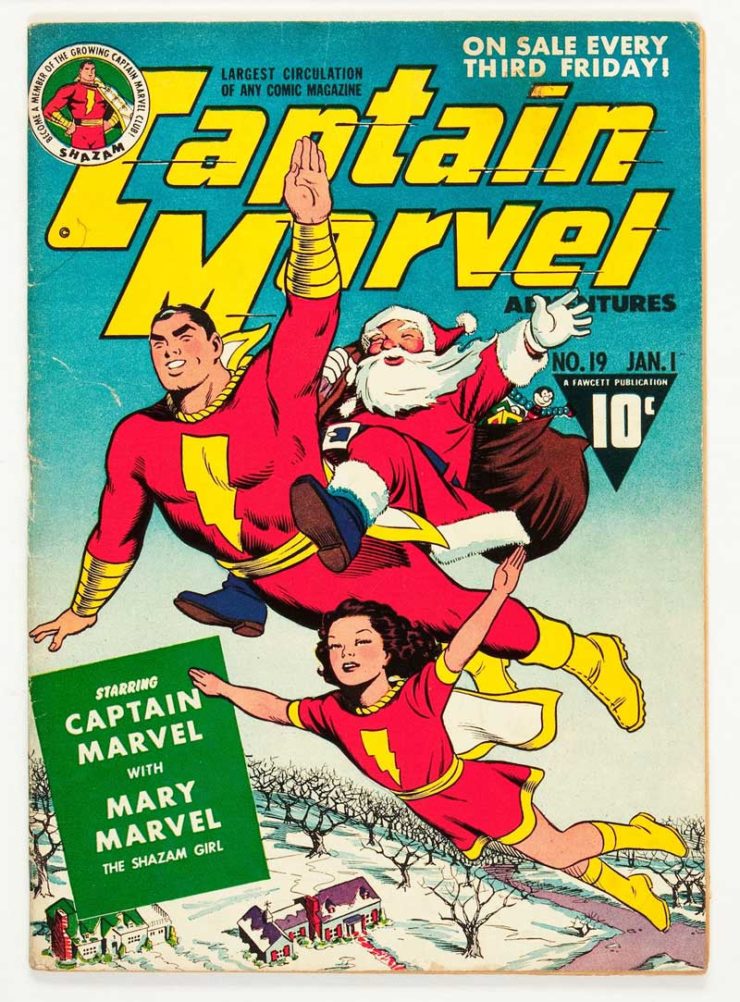

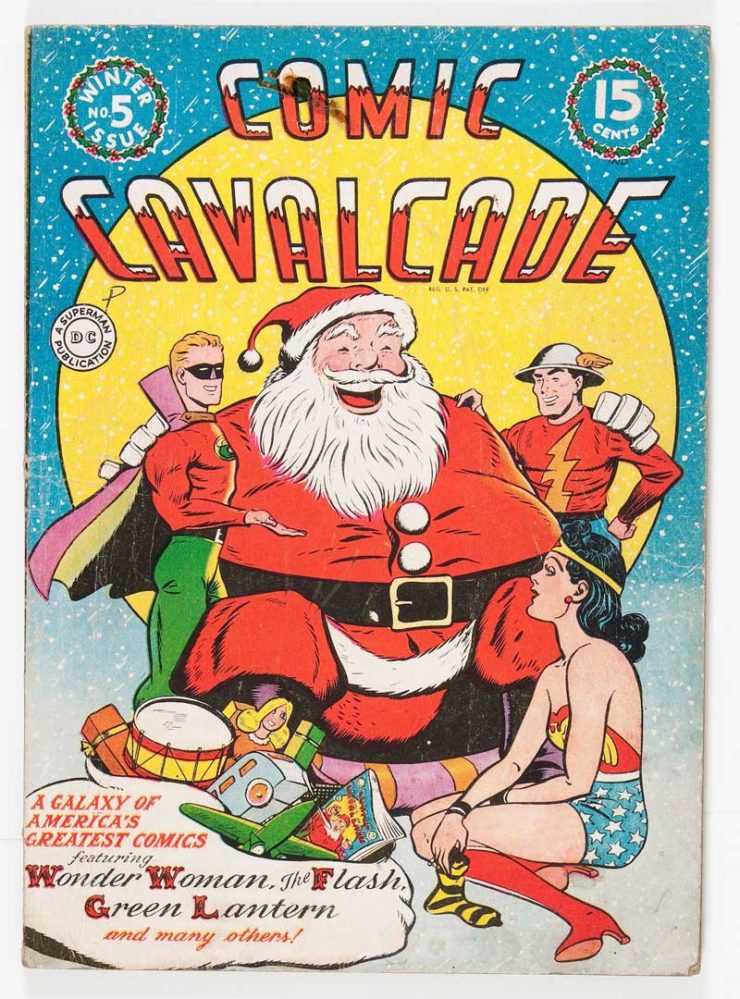

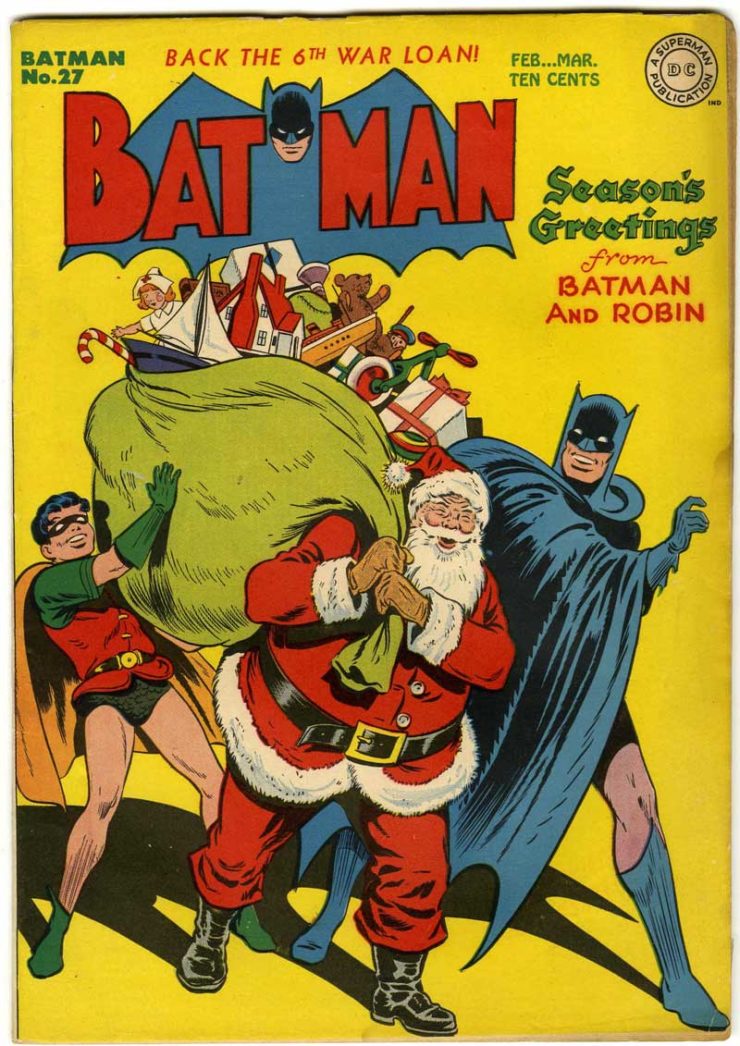

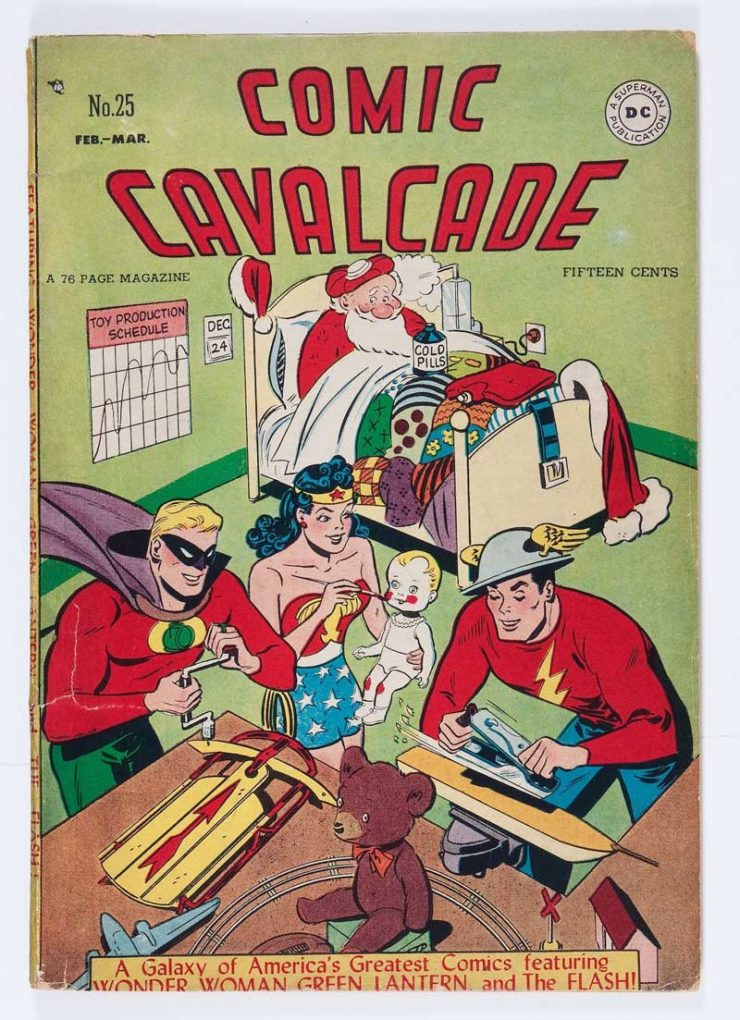

Covers spanning 1941 to 1948 (figures 1-4) depict Santa assisted in his task of delivering gifts by a wide variety of superheroes. In figure 4, his role is appropriated (albeit temporarily) by superheroes who pitch in with toy construction as Santa is ill and abed in the background. These are all conventional depictions of Santa, and the 1945 Batman cover incongruously also exhorts readers to “back the 6th war loan.”

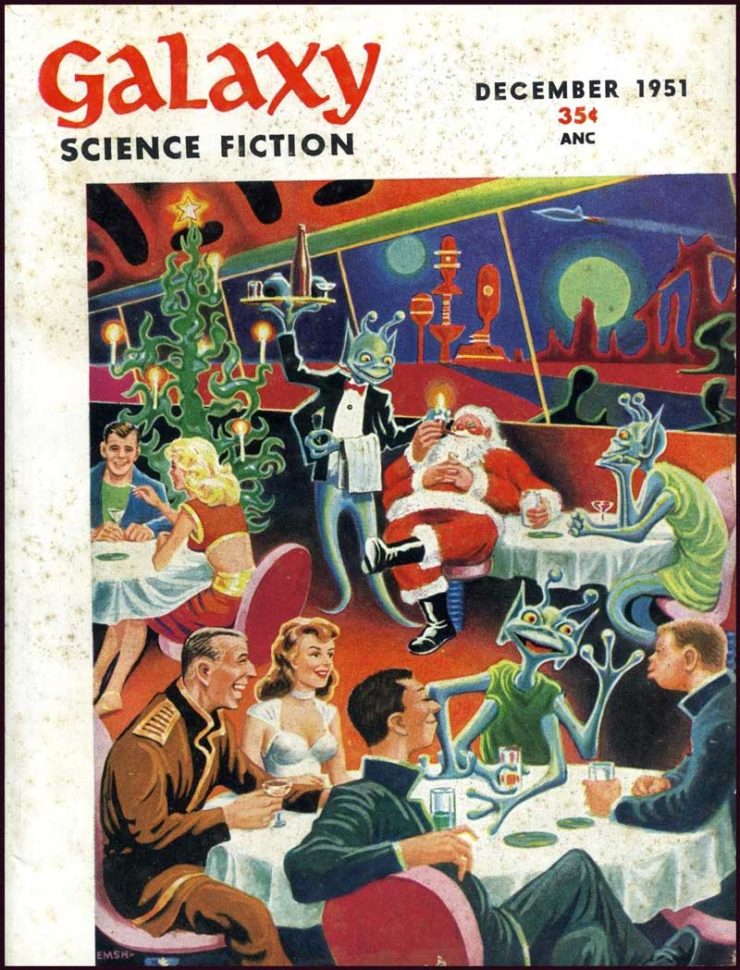

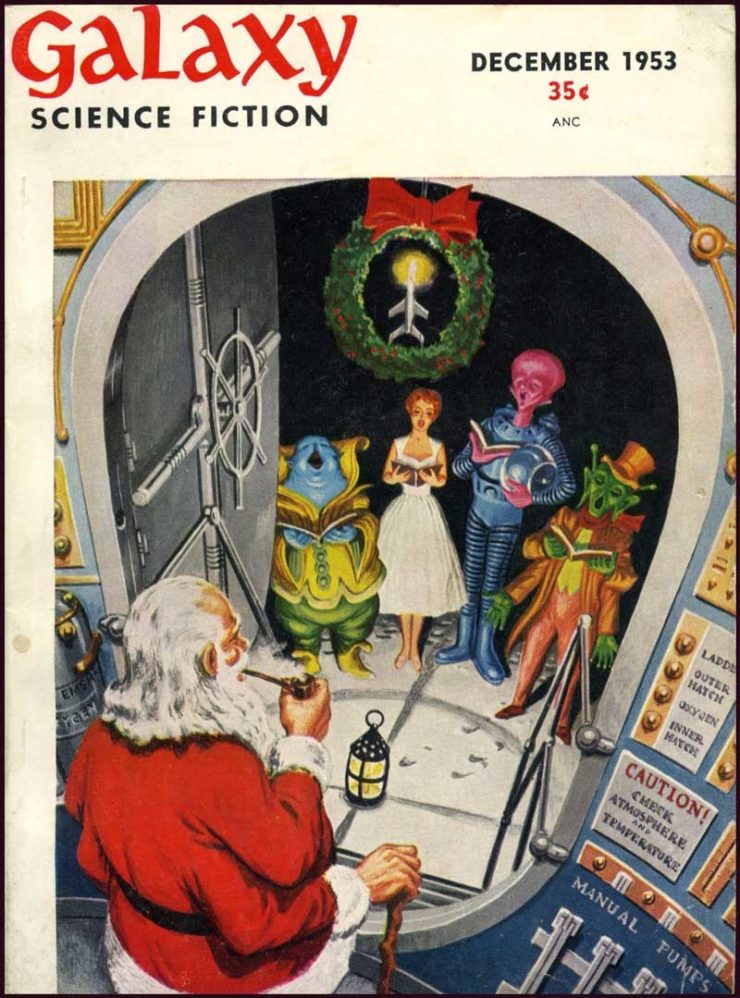

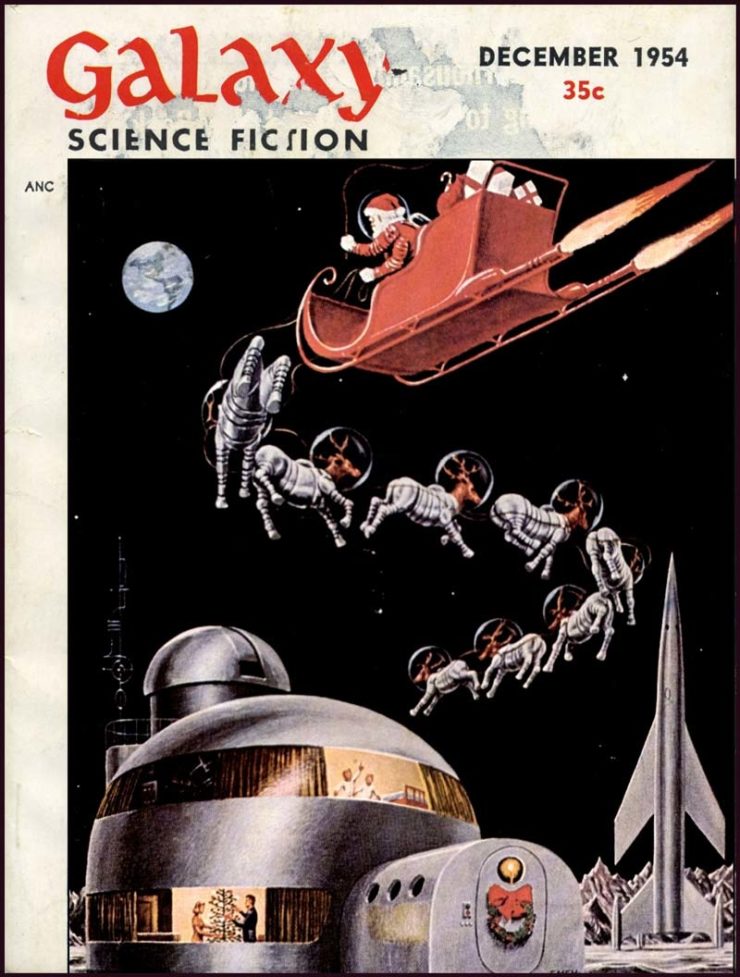

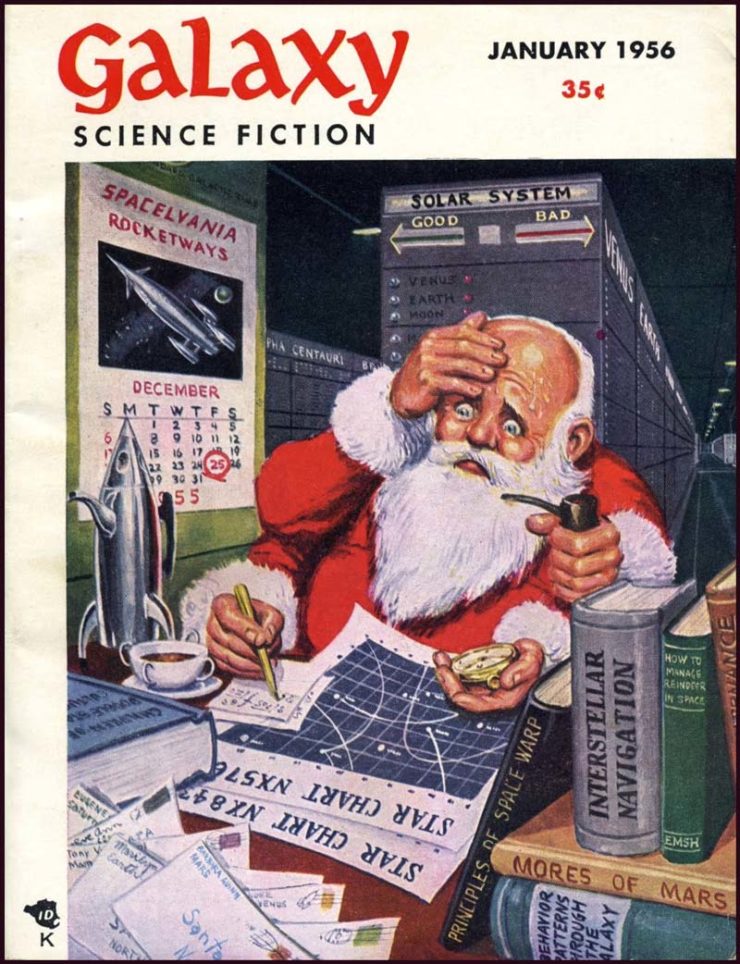

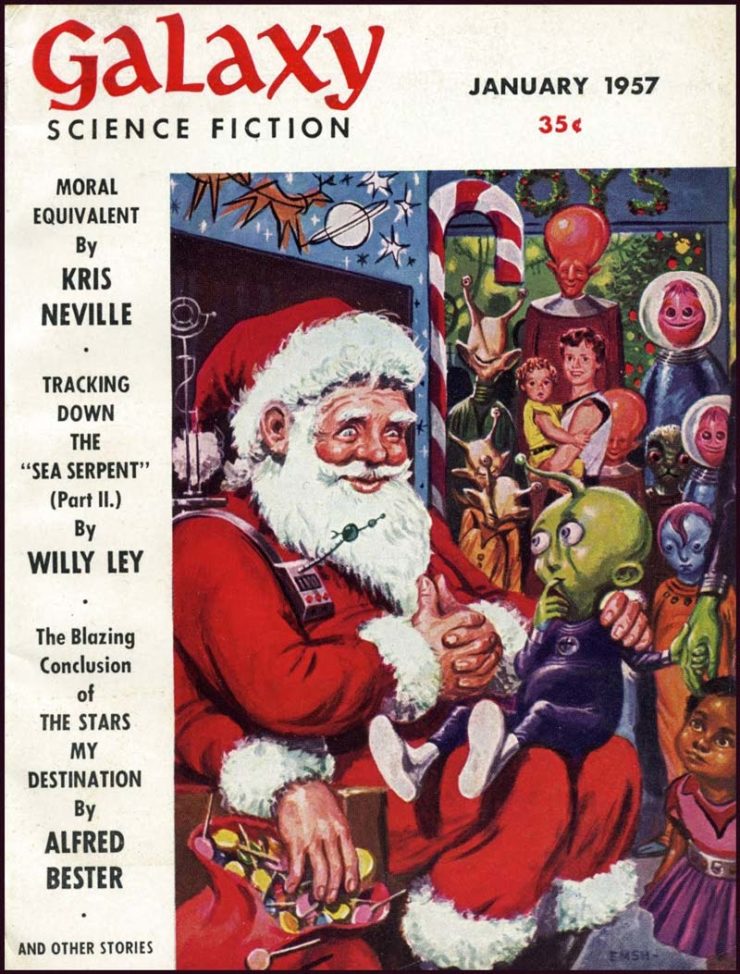

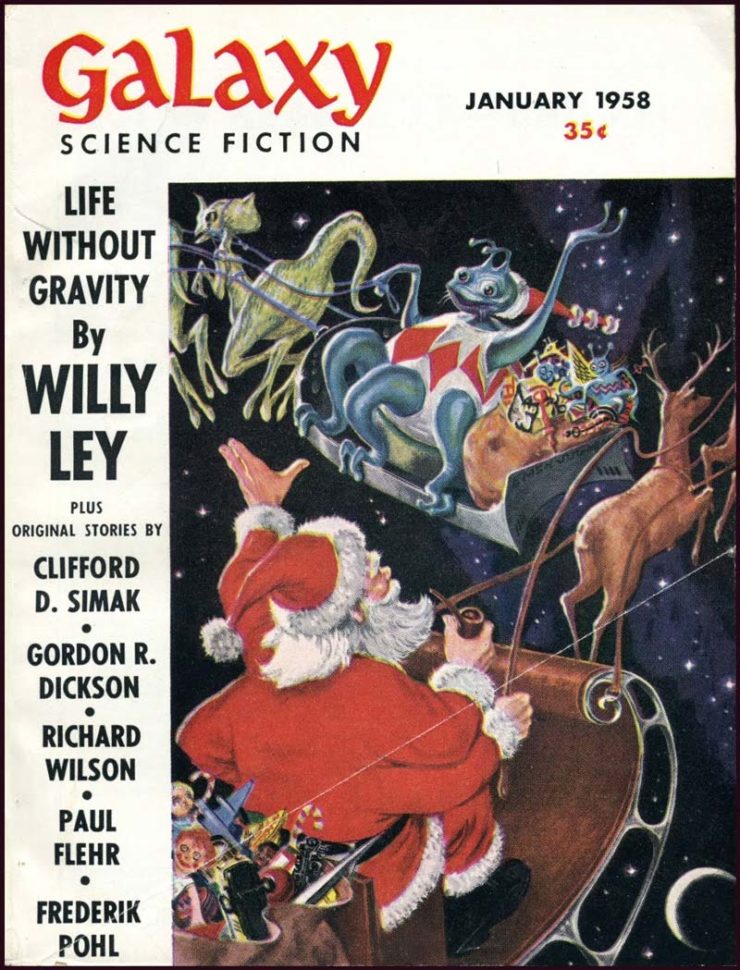

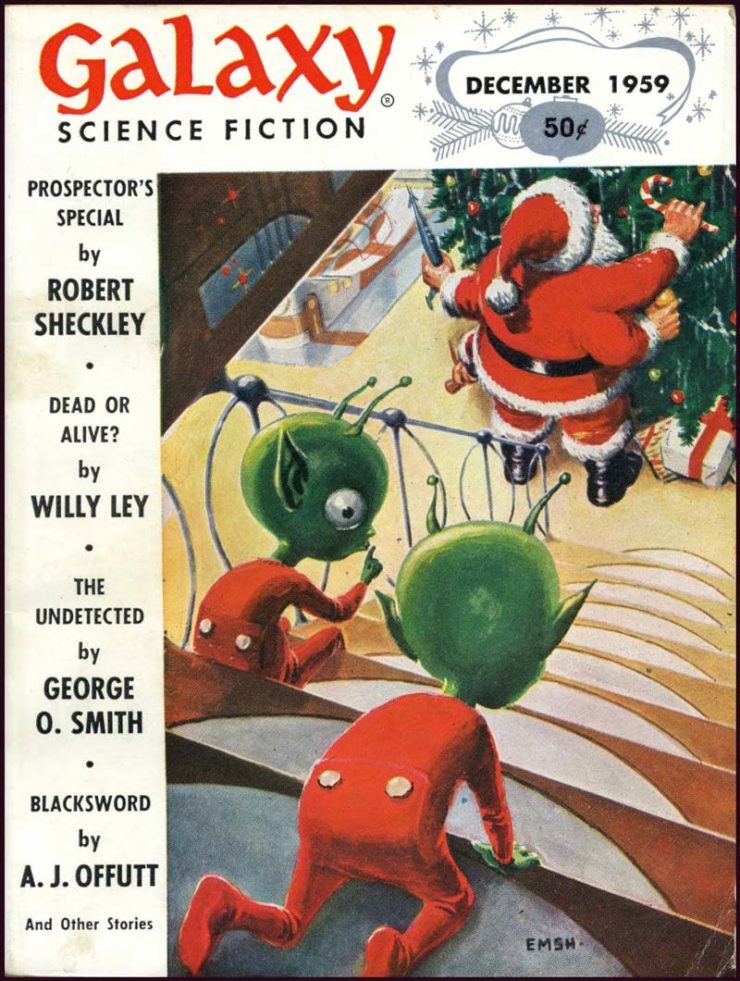

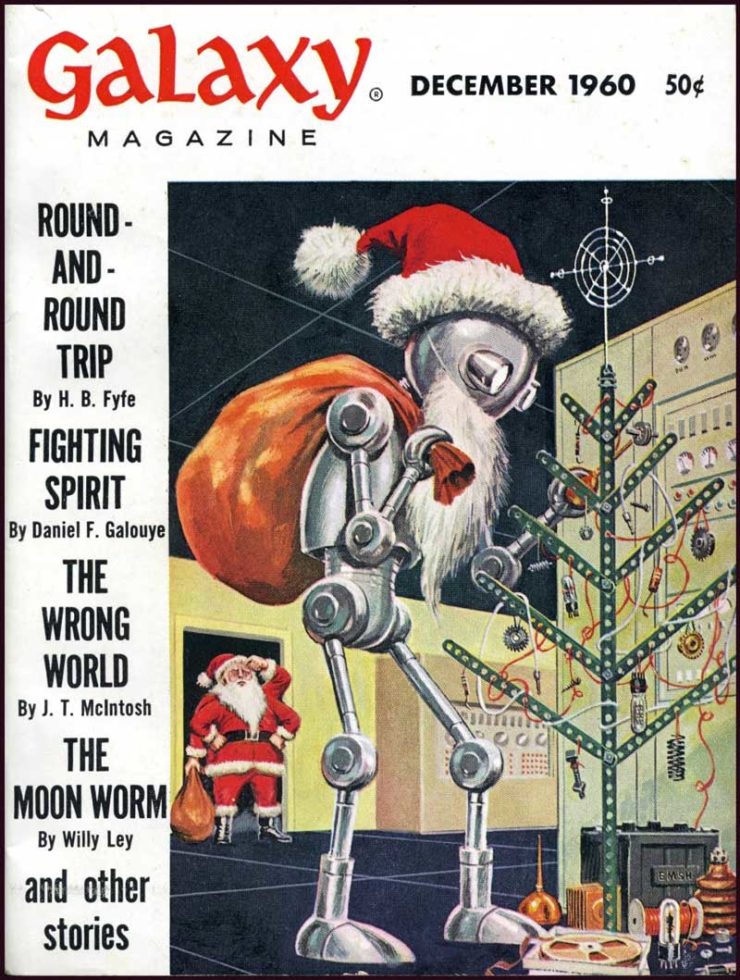

The decade 1951–1960 featured several covers from Galaxy Science Fiction magazine by Edmund Alexander Emshwiller (1925–1990), also known as Emsh. All of his Santas superficially resemble the traditional Santa, a jovial, fat, pipe-toting, balding, white-haired and white-bearded fellow in the customary red suit (figures 5-12). Notably, his Santa has four arms. However, even over this relatively small period of time, Emshwiller depicts important changes in Santa.

The 1951 cover conventionally depicts Santa having a drink, albeit with a mixed bag of humans and aliens, being served (and having his pipe lit) by a very alien waiter in a tuxedo next to an alien Christmas tree, in a futuristic building or vehicle and with an equally futuristic and possibly alien window view.

Two years later, the 1953 cover is also innovative, with Santa standing just inside a spaceship airlock (which is signposted with warnings to check the external environment before opening the door) and listening to four carolers of whom only one is human. Overhead, a wreath contains a candle in the shape of a spaceship.

The 1954 cover illustrates Santa taking off from a futuristic base that is off the Earth, possibly the moon, with Earth visible in the background. His vehicle is rocket propelled and is assisted by reindeer who, like Santa, have donned space suits.

Two years later, the cover shows a worried Santa attempting to plot courses across space, presumably in order to hand out gifts. He is aided by coffee from a spaceship-shaped dispenser, a fob watch, navigation textbooks, a calendar, and a huge computer that is labeled not only with names of planets, but with names of stars, subdivided further by the labels “good” and “bad.” Transport technology has advanced in that one of the books on his desk is Principles of Space Warp.

The 1957 cover portrays Santa playing with an alien baby and dispensing gifts not only to humans but also to aliens who are so different that they cannot even breathe the same air as Santa, and therefore wear space suits.

In the following year, Santa shares his task with an alien and octopoid Santa who crosses his path in space while being pulled by equally alien equivalents of reindeer, which appear to be vaguely saurischian with kangaroo-like hindquarters.

The 1959 cover is similar in theme to the 1957 cover, with Santa arranging toys on a Christmas tree while being watched by two alien toddlers. Christmas’s characteristic green is the predominant color used in the depiction of aliens in this series of illustrations.

The December 1960 Galaxy cover shows a puzzled Santa in the background gazing at a robot Santa who has seemingly supplanted the organic Santa and who adorns an angular, inorganic Christmas tree with bits of machinery, such as nuts, bolts, and springs.

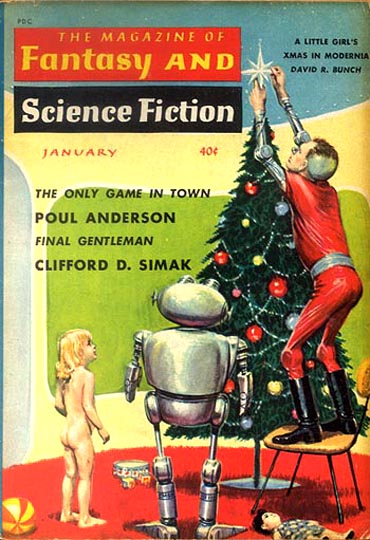

Emshwiller’s cover the following January for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction features a young girl and a small robot watching a cyborg decorating a Christmas tree. The cyborg has prosthetic arms, legs, nose and a metal patch replacing part of his skull. The same theme is also reflected in the cover of the 1958 Popular Electronics magazine with male and female robots decorating a Christmas tree, accompanied by a robotic pet dog (not pictured).

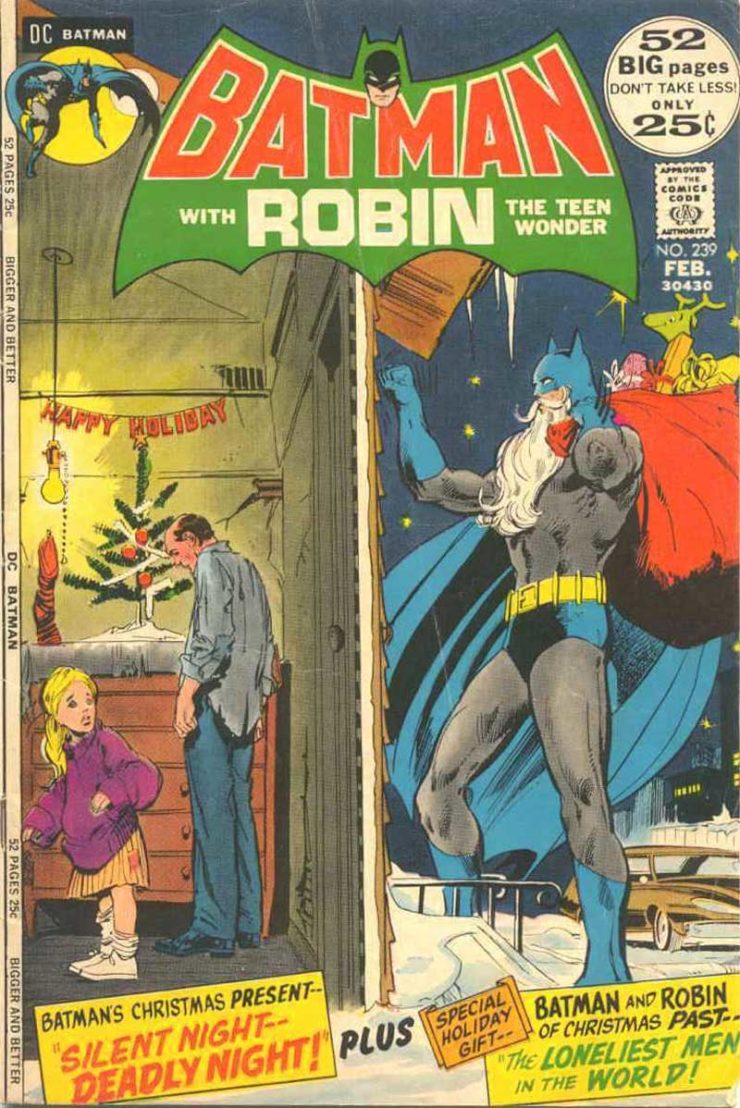

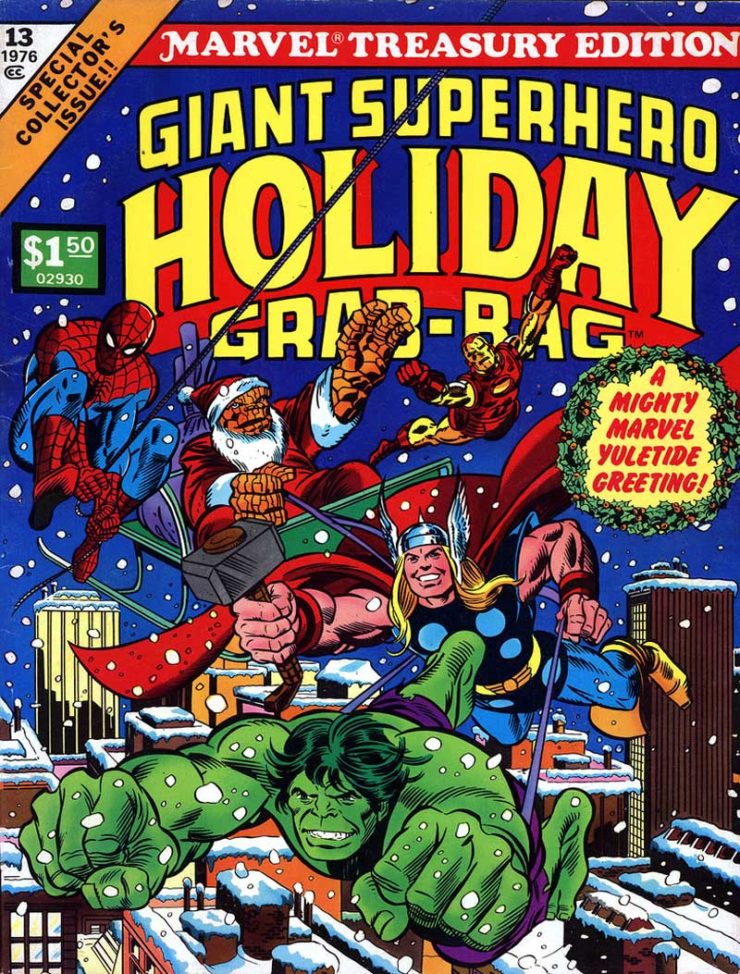

Skipping forward, the next cover from 1972 constitutes a watershed with Santa’s role appropriated by Batman. Similarly, a 1976 cover shows the monstrous Thing (one of the Fantastic Four) dressed as Santa. These two covers seemingly prefigure Lyotard’s postmodern as “incredulity towards metanarratives,” in that Santa is rejected and traded for a superhero.

These covers indirectly intimate incredulity toward Santa himself, an attitude that persists in the remaining illustrations. Thus, a 1986 cover portrays a sleazy Santa replete with shades, a cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth, and a handgun in a finger-less glove.

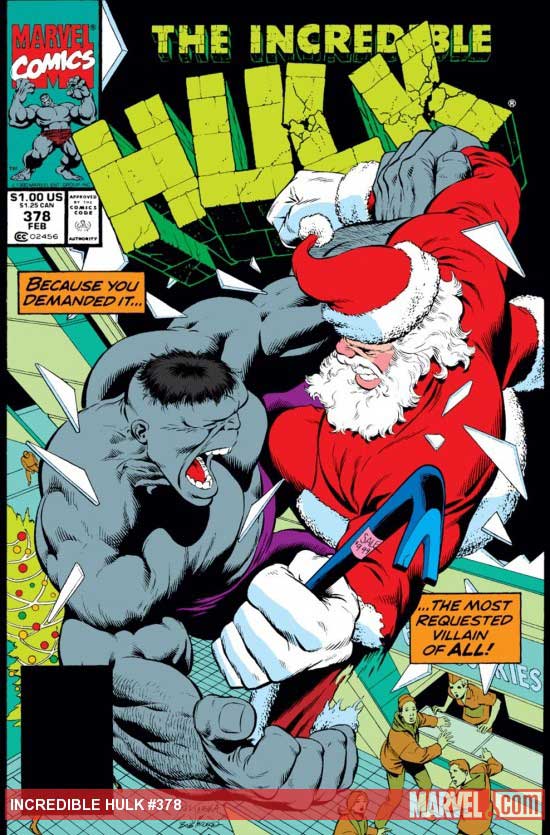

Similarly, a 1991 cover depicts Santa fighting the incredible Hulk with a crowbar (figure 17); it must be remembered that the Hulk, while constituting an antihero, is ultimately one of the good guys.

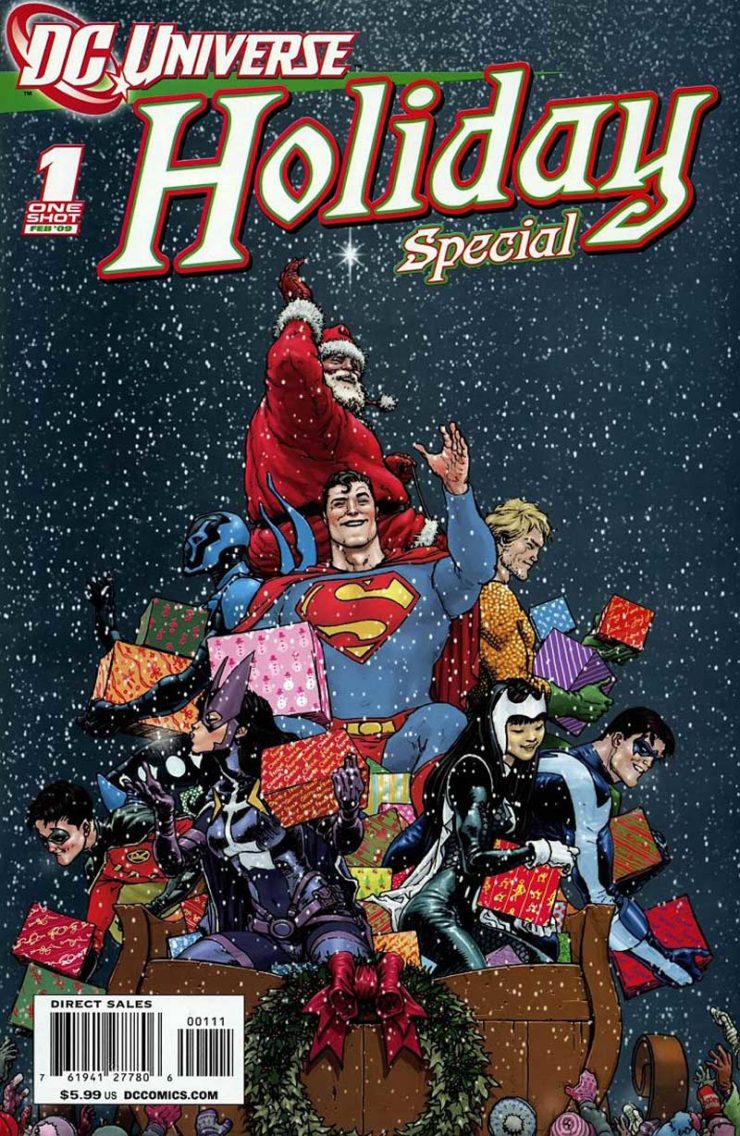

The next cover from 2008 is a single acknowledgment to the past with Santa being helped by a group of superheroes.

But our final cover from 2009 is the ultimate postmodern rejection of the Santa metanarrative: a haggard Santa stares at the reader in consternation while being arrested by Judge Dredd, who sneeringly admonishes him: “Housebreaking—twenty years, creep!”

Asimov noted that “[t]he history of science fiction can be divided into four eras: 1. 1815–1926; 2. 1926–1938; 3. 1938–1945; and 4. 1945 to present,” and these eras were respectively the relatively primitive, adventure-dominant (e.g. Wells and Burroughs); 1938-50 science-physicist-engineer dominant (e.g. Campbell and Astounding); 1950-65 sociology-dominant (e.g. Wyndham and Bradbury) and 1966 to the present being style-dominant, with narratives of deliberately enhanced literariness along with the development of sub-genres within sf itself.

This relatively small sample of magazine covers within the genre has exposed similar tropes and aspirations, which have mutated over the decades. The early covers were unassuming and fêted a conventional Santa who consorts with other and equally mythic characters such as superheroes. Santa is arguably a superhero, doing good by using powers that are beyond human comprehension, such as the near-instantaneous delivery of uncountable presents.

This era was followed by the inveiglement of science and technology, exposing the genre’s emphasis during this era which “valorizes a particular sort of writing: ‘Hard sf,’ linear narratives, heroes solving problems or countering threats in a space-opera or technological-adventure idiom”. (Roberts 194)

The next era of covers just predated the rise and popularization of postmodernism, leading to a refutation of the Santa metanarrative, in the same way that postmodernism resulted in skepticism toward all metanarratives.

SF magazines and comic books can be said to reflect scientific progress, which portrays aliens, computers, androids, robots and cyborgs as the new, frightful and mysterious adversaries and “we have populated these new unknowns with monsters and ogres that could well be the close relatives of the trolls and ogres of folklore fame. In that sense . . . sf is modern folklore” (Schelde 4).

In conclusion, the mythical Santa metanarrative has been rejected outright by magazine covers or replaced by superheroes who temporarily don the Santa mantle in order to keep the myth alive, a loss of innocence that is as inevitable as it is sad.

Roberts, Adam. The History of Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Asimov, Isaac. “Social Science Fiction.” Modern Science Fiction: Its Meaning and Its Future. Edited by Reginald Bretnor. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1953.

Clynes, Manfred E. and Nathan S. Kline. “Cyborgs and Space.” Astronautics September (1960): 26-27, 74-75.

Lyotard, Jean-Francois. The Post-Modern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Schelde, Per. Androids, Humanoids, and Other Science Fiction Monsters: Science and Soul in Science Fiction Films. New York: New York University Press, 1993.

Originally published December 2012, and again in December 2016.

Victor Grech lives in Tal-Qroqq, Malta. A version of this article appeared in the December 2012 issue of The New York Review of Science Fiction, available through Weightless Books.